March 30, 2021

Second Exodus

This story begins with a phone call from my cousin Morris. It also begins with something I almost never do when getting a phone call from my cousin Morris.

I answer it.

Right away, I am reminded of the benefit of screening.

“You know what your problem is,” he begins without even saying hello “I’ll tell you what your problem is.”

I don’t say anything because I know Morris, who has quickly gotten over the shock of me having answered the phone, is going to barrel on.

“Your problem is you go out with Ashkenazi women instead of finding yourself a nice Egyptian Jewish woman. Somebody with similar history, food and culture. Someone you have something in common with.”

Morris, I should mention, married a very nice Ashkenazi woman.

I say “You’re right. I never thought of that.” Which I thought might end the discussion.

But it didn’t.

“I know of someone,” he says.” I have her number.”

“Morris,” I reply in what I hope is my sternest tone.

But then he says something which we both know carries a lot of weight.

“You might get a good story out of it.”

Adele Harari and I spend the first thirty minutes of our date playing Egyptian Jewish geography. Not because we want to find people we have in common. But because we want to make sure we aren’t cousins.

We’re not.

Not really.

We then, because it is the middle of the Jewish holiday of Passover, gingerly probe our respective food restrictions and realize that although neither of us believe in anything, we both ask the waitress to remove the verboten croutons from our caesar salads. Morris is right. There is a lot of commonality.

“It’s nice not to have to explain to someone what meggadara is,” I say with a smile.

“I don’t know,” she replies “I like to play up the Egyptian thing. Men think it’s exotic.”

“Not so much,” I say with a laugh.

“Especially this time of the year,” she continues, ignoring my tease, “I have my own coming out of Egypt story. You must have one too.”

“Of course,” I said.

But I’m not sure I did.

My favorite part of the seder is L’dor Va Dor.

In every generation we are to regard ourselves as if we ourselves had gone out of Egypt.

I love that. Because this is when my mom would say “I did go out of Egypt.”

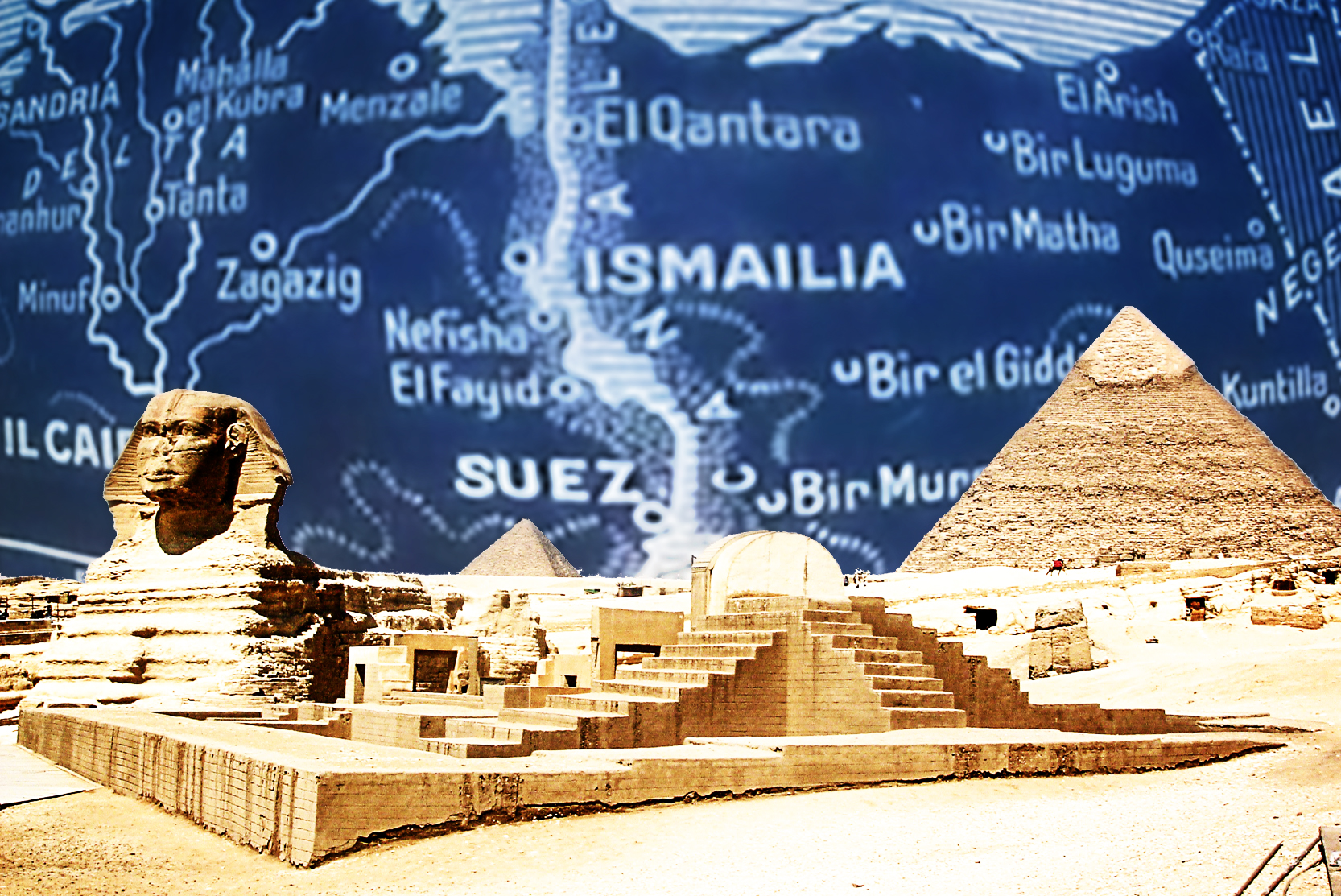

My mother and father, my aunts and uncles, were once part of an 80,000 strong Jewish community in Egypt. Most left, or were kicked out, after the 1956 Suez Crisis. Their departure, often, like their forefathers, without having the time to wait for the bread to rise, is colloquially referred to as the Second Exodus.

So, there should be a story. But, growing up, it never occured to us to ask. It was just part of their history. And later, when my nieces began to take a real interest, my mother had forgotten many of the details and, more importantly was too hungry and tired to start recounting old tales.

So we were left with short recollections, a train ride, melted down jewelry, my Tante Lilianne being arrested, and scant details which often changed as the years went by. There was not much of a story.

Adele Harari, on the other hand, had a great exodus story. Her family owned a large store which sold kitchenware. Harari’s was known all over Cairo as the place to buy high end flatware imported from Belgium. With his store about to be nationalized by the Egyptian government, Marcel Harari, Adele’s grandfather, sold the store to his general manager, Achmed Mawfouz, a Copt who had worked in the store for nearly forty years, for ten cents on the dollar. The sale, which on the face looked more like a steal, came with the pledge from Mawfouz to smuggle the Harari family who, falsely accused of being communists, had been unable to get, by bribe or otherwise, an exit visa, out of the country. Mawfouz had instructed the Harari’s to pack lightly and be ready to move at the shortest notice as he awaited notice from the Egyptian fisherman whose trawler would take them to Cyprus. The knock on the door came, the Harari’s swear on a stack of bibles, when they were reciting Dayeinu. They stole out in the middle of the night with the clothes on their back. It was six weeks later, in an Israeli absorption camp, that Marcel Harari remembered that they had left without finding the afikoman that Harari had hidden in a loose floorboard in the dining room. He managed to send a message to his ex manager who went back to the Rue Roi Farouk apartment and retrieved the embroidered table cloth- the rats had eaten the middle matza- who then took a picture of himself holding the table cloth.

Adele Harari handed me her phone where she had, in her photo folder, a picture of the original photograph.

It was a good passover story.

At the last seder we ever had with my mother, who died peacefully in her sleep a week later, Rena, who had earlier dramatically rapped the Four Questions, decided to press her luck and ask again about our family’s exodus from Egypt. She waited until after my mother had finished her plate of ashkenazi food which now graced our table every passover.

“Nona,” she implored. “Tell us the story about when you left Egypt.”

“It is ancient history.” She said helping herself to a matza meal roll which, on day one we convinced ourselves almost tasted like the real thing “what do you want to know?”

“Is there a story?” She asked.

“The story,” she said “is we were in Egypt. Then we came to Canada and made a life for ourselves.”

“That’s all?” Asked Rena.

My mother didn’t say anything for a few seconds. At first I thought she had fallen asleep.

Then she shrugged her arthritic shoulders and said

“What else is there?”

In the months and years following my mother’s death, I made an effort to contact my aunts and uncles and cousins both on my mother’s and father’s side in order to glean more details about how they left Egypt. Everyone, it turns out, was fired on the same day. Their bank accounts were frozen and my Tante Lilianne did spend some time in prison. My father, though born in Egypt, was Ashkenazi and somehow managed to land himself a passport. Everyone else scrambled to get a laissez passer and then find a country which would take them in. Some made it to Switzerland, some to France, and some, like my father, to Italy. Eventually most made it to displacement camps in Israel- the only place that had really opened their borders. All described their life in Israel as being really hard. Perhaps it is the passage of time but none of their stories were told with any bitterness. If anything, they all remembered their life in Egypt as halcyon days. It had been a place which was good for the Jews. And then it wasn’t. In their mind, they had had a good run. Most ended up in Montreal, Canada. I don’t suppose any had ever even seen snow before. They had children and dressed them in snow suits and scarves and mittens. They shoveled driveways and went tobogganing. I'm not sure how they did it.

It was not a story, like Adele Harari’s, you could dine out on. But it was their story. Their story of having made a life for themselves. For their children and for their grandchildren. Their story was one of looking forward and not backward.

And really, what else is there.

The end.